Greetings from the Big Geodata Newsletter!

In this issue you will find information on Geospatial Reasoning by Google Research for integrating generative AI with geospatial foundation models, the Sedona STAC Reader for streamlining large-scale geospatial data analysis, the advantages of tensor-based models over tables for scientific big data, NVIDIA Earth-2’s approach to AI-driven flood risk assessment, and the LUIcube dataset tracking global land-use intensity from 1992 to 2020. Our Geospatial Computing Platform user story on localized deformation detection and prediction in urban environments using SAR and deep learning is also here!

Happy reading!

You can access the previous issues of the newsletter on our web portal. If you find the newsletter useful, please share the subscription link below with your network.

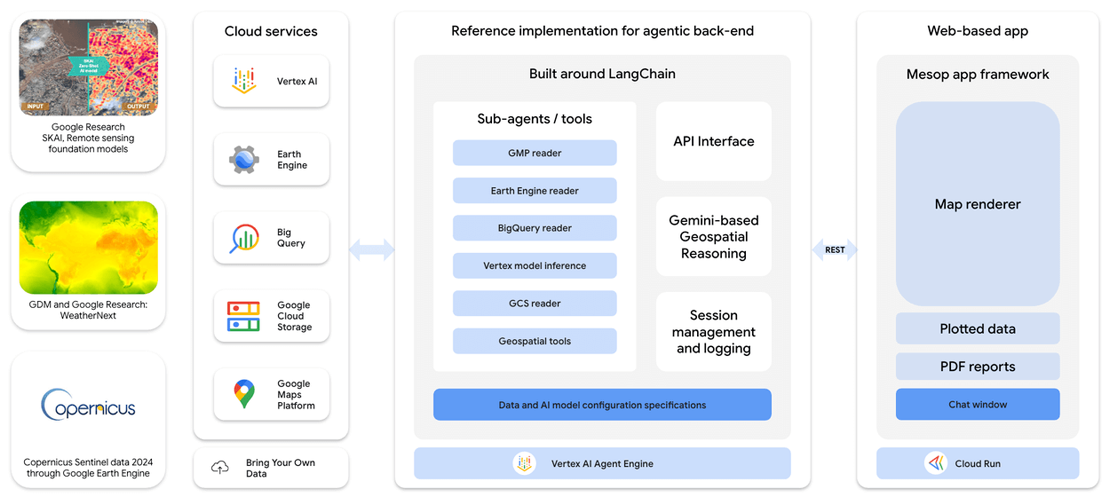

Geospatial Reasoning: Combining Generative AI and Foundation Models for Spatial Insights

Image credits: Google Research Blog, 2025

Geospatial Reasoning, introduced by Google Research, brings together generative AI and multiple geospatial foundation models to advance the way spatial data is analyzed and interpreted. Instead of relying on a single model, the framework integrates Google's Gemini language models with domain-specific models like the Population Dynamics Foundation Model (PDFM) and a new Remote Sensing Foundation Model, enabling deeper exploration of complex geospatial relationships. This system uses a agent-based orchestration method, allowing users to pose natural language queries about geographic phenomena. The models then coordinate to retrieve, synthesize, and present meaningful answers and visualizations based on satellite imagery, aerial photos, and environmental datasets. By leveraging multimodal embeddings, the framework supports tasks across diverse fields such as disaster response, urban planning, and environmental monitoring. Geospatial Reasoning highlights how combining language and geospatial models can improve accessibility to large, distributed datasets, helping researchers and planners interpret spatial patterns with greater clarity and efficiency.

Learn more about Geospatial Reasoning and its applications here. Explore Google's broader research on AI and geospatial technologies here.

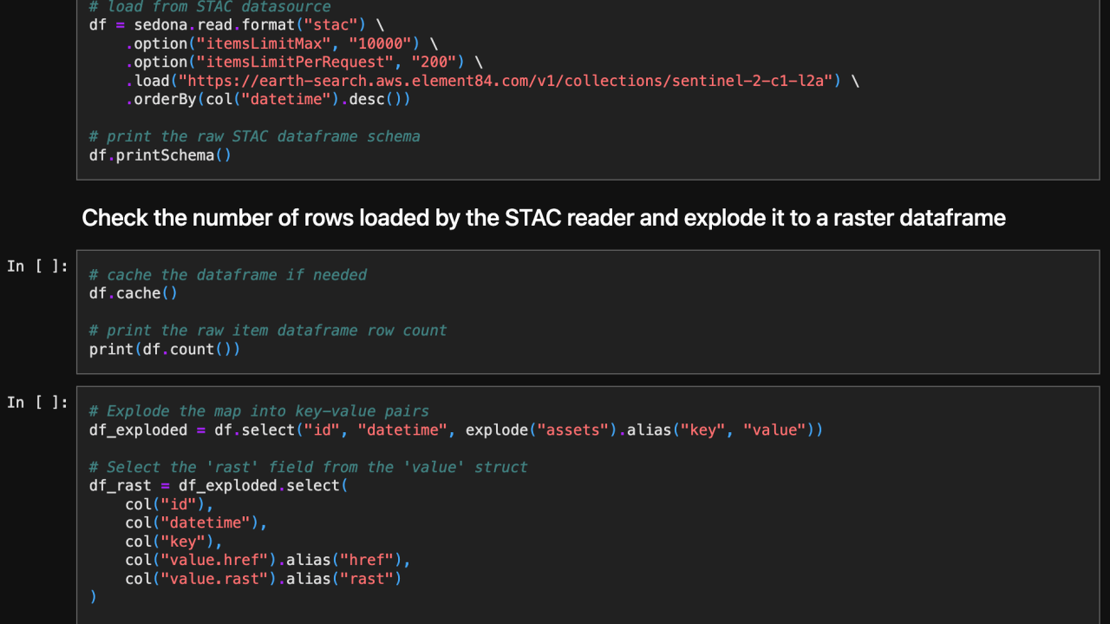

Sedona STAC Reader: Simplifying Geospatial Analytics with Apache Sedona

Image credits: Feng Zhang, LinkedIn, 2025

The latest release of Apache Sedona 1.7.1 introduces the STAC Reader, aimed at simplifying the ingestion and analysis of SpatioTemporal Asset Catalog (STAC) datasets within large-scale geospatial workflows. Developed to enhance cloud-native geospatial analytics, the STAC Reader provides an efficient way to access and query imagery and raster data from STAC-compliant endpoints without complex preprocessing steps. STAC datasets, such as Sentinel-2, Landsat, and other Earth observation products, contain rich metadata and references to large collections of assets. Traditionally, working with these datasets involved time-consuming tasks like manual downloading, parsing, and structuring of imagery. With the new STAC Reader, Sedona users can now directly load and analyze STAC datasets at scale using Apache Spark, leveraging Sedona’s distributed spatial computing capabilities. This new feature simplifies workflows and improves performance, scalability, and cost-efficiency by supporting direct, on-demand querying of extensive geospatial collections stored in cloud object storage.

Learn more about the Sedona STAC Reader and its capabilities here. Explore Apache Sedona and its geospatial processing tools here.

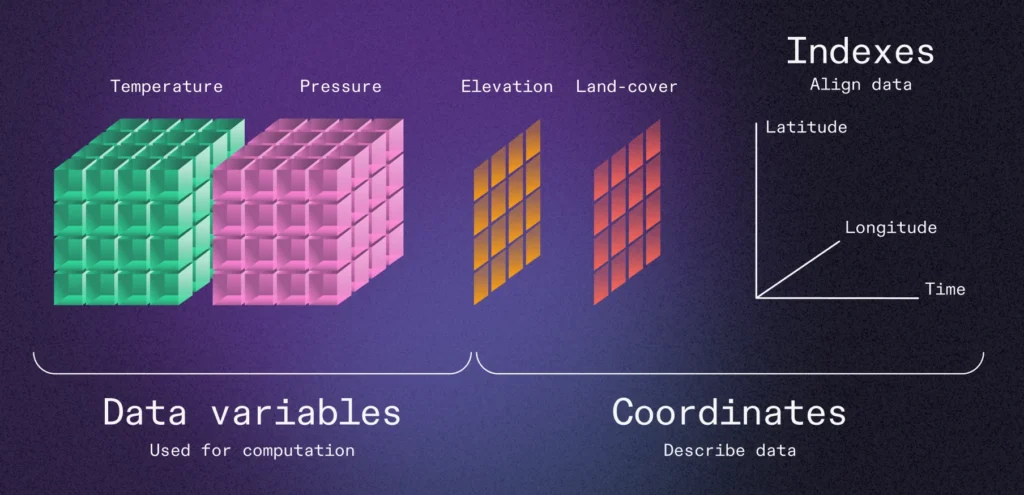

Tensors vs Tables: Rethinking Data Models for Scientific and Cloud-Native Big Data

Image Credits: Earthmover, 2025

Traditional tabular data models, structured into rows and columns, have served data analytics needs quite well for long time. However, their limitations become increasingly clear for complex, multidimensional scientific data. In the Earthmover blog "Tensors vs Tables," the case is made for shifting to tensor-based or multidimensional array-native models to meet the demands of modern data processing. Storing these datasets in flat tables often results in redundant information, cumbersome queries, and inefficient computation. By contrast, tensor structures preserve the natural organization of data, allowing more intuitive slicing, querying, and analysis. This shift is particularly important for big data and cloud-native architectures, where efficient data access and transfer are critical. Managing scientific big data in a tensor-native format reduces I/O costs, accelerates data retrieval, and enables parallel computing frameworks like Dask and Apache Spark to operate more effectively. Embedding tensors within traditional tables, even using advanced formats like Apache Arrow or Parquet, creates technical debt: retrieval becomes inefficient, metadata becomes harder to manage, and scaling across distributed systems becomes more complex.

Read the full article with detailed performance benchmarks on different approaches here.

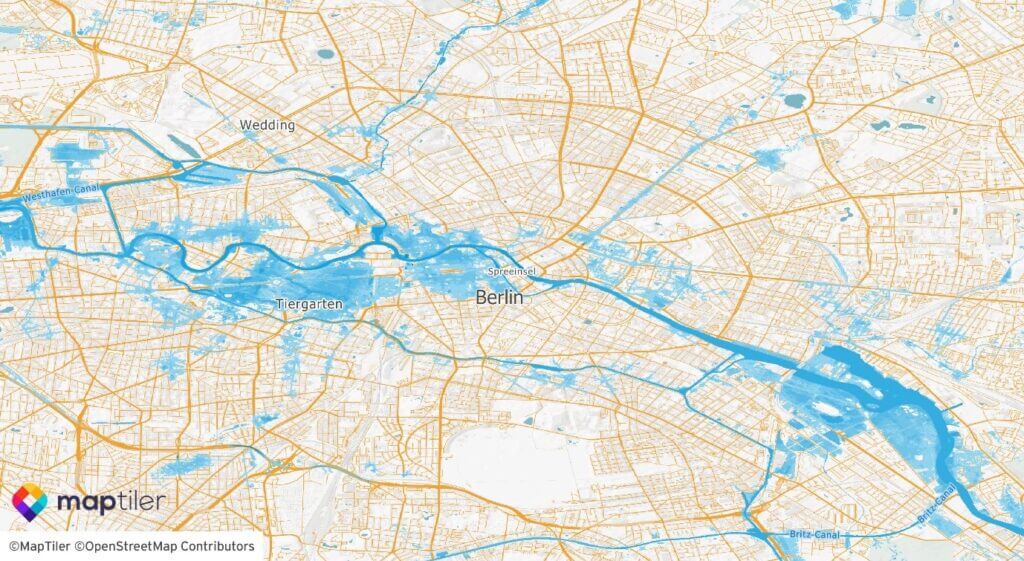

Powering Flood Risk Assessment with NVIDIA Earth-2

Image credits: NVIDIA, 2025

NVIDIA Earth-2 is reshaping flood risk assessment by combining AI-driven weather modeling with scalable geospatial analysis. Traditional flood models depend on limited historical data, making predicting rare, catastrophic events like 1-in-200-year floods difficult. To improve preparedness, JBA Risk Management collaborated with NVIDIA to create the Huge Ensemble (HENS) pipeline, producing thousands of physically realistic weather scenarios. Built on Earth-2’s AI-accelerated software stack, the HENS pipeline generates synthetic weather datasets faster and at larger scales than conventional methods. Using just 110 GPU hours on NVIDIA L40s GPUs in the cloud, the team simulated 300 years of atmospheric data, which was then fed into hydrological models to estimate flood risk. This approach enables a detailed understanding of flood risk distributions, helping industries like insurance and urban planning better manage extreme weather impacts. By leveraging AI and cloud-native infrastructure, NVIDIA Earth-2 enables faster, more resilient flood risk modelling, supporting better decision-making and long-term climate adaptation strategies.

Learn more about NVIDIA Earth-2 and its flood risk modeling capabilities here. Explore NVIDIA’s broader Earth-2 initiatives here.

Upcoming EVENTS

- CRIB Training: Introduction to Docker

ITC, Enschede, 14 May - SURF Research Day

Hilversum, 20 May - Open and FAIR in NES

Utrecht, 22 - 23 May - CRIB Training: Introduction to openEO for Cloud-based Geoprocessing

ITC, Enschede, 4 June - Living Planet Symposium 2025

Vienna, 23 - 27 June - SURF Training: High-Throughput Data Movement and Data Abstraction

Utrecht, 27 June

The "Big" Picture

Image credits: Matej et al., 2025

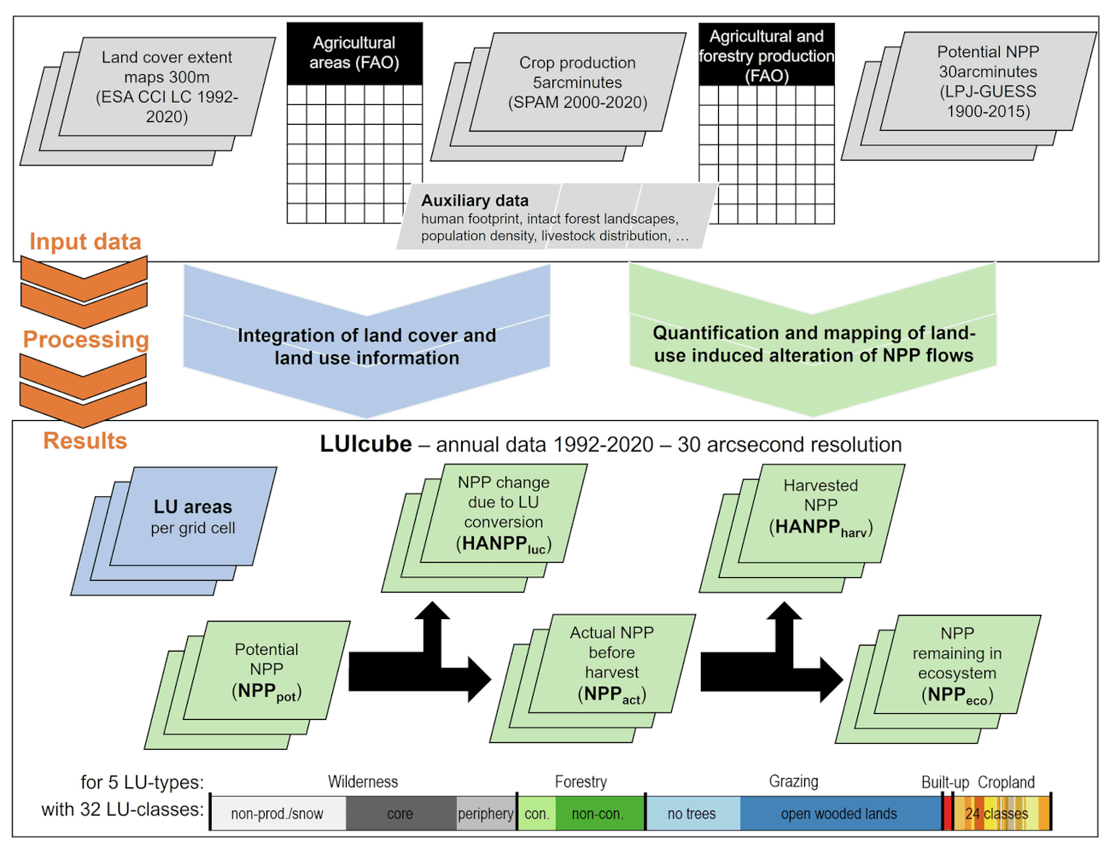

The newly released LUIcube dataset provides an extensive global land-use data cube, documenting annual human land-use intensity from 1992 to 2020 at a high resolution of 30 arcseconds (~1 km²). Developed using the Human Appropriation of Net Primary Production (HANPP) framework, this dataset quantifies global human impacts on terrestrial ecosystems. LUIcube classifies land into 32 detailed categories, aggregated into five major land-use types: cropland, grazing land, forestry, built-up land, and wilderness areas. It combines satellite-based land cover data from ESA's Climate Change Initiative with robust statistical data from the FAO and other authoritative sources, ensuring high accuracy and consistency. By capturing annual dynamics in biomass harvest, land conversion, and ecosystem productivity, LUIcube enables studying human-induced environmental change. The dataset supports researchers, policymakers, and conservationists in understanding long-term trends, drivers, and ecological impacts of global land-use changes, essential for shaping sustainable land management strategies.

Explore the full LUIcube study and access the dataset here.

Matej, S., Weidinger, F., Kaufmann, L., Roux, N., Gingrich, S., Haberl, H., Krausmann, F., and Erb, K. (2025) A global land-use data cube 1992–2020 based on the Human Appropriation of Net Primary Production. Scientific Data, 12(1). doi:10.1038/s41597-025-04788-1.